This post explains, with data and case-backed examples, why disruption and enforcement actions against criminal domains are often far more effective than merely listing those domains in abuse datasets (such as Spamhaus). The core argument is simple: When you terminate the attacker’s infrastructure at the DNS/hosting layer, you stop victimisation upstream. When you list it, you only reduce exposure downstream - and often too late.

The problem: domains are the attacker’s steering wheel

In modern cybercrime, domains are not just “indicators.” They are operational assets: they anchor phishing kits, command-and-control endpoints, scam storefronts, credential collection pages, and the distribution infrastructure that feeds them. That is why frames DNS abuse in actionable categories like phishing, malware, botnets, and pharming - i.e., harms that are enabled by domain names and DNS resolution.

What defenders often call “domain abuse” is really a chain of dependencies:

- the domain (registrar/registry control)

- the DNS configuration (nameservers, records)

- the hosting layer (where content and scripts live)

- the delivery layer (email/SMS/social/search/ads)

- the user interface layer (URLs, lookalikes, trust cues)

A blocklist typically touches only the last two layers. Disruption and enforcement can hit the first three - the layers where the attacker’s operation runs.

Passive listing: necessary, scalable - and inherently limited

Abuse datasets and blocklists exist for good reasons: they are scalable, automatable, and easy to integrate into email gateways and secure web stacks.

For example, Spamhaus’ Domain Blocklist (DBL) is explicitly positioned as a reputation-based list of domains used in spam and malicious activity (phishing, fraud, malware distribution), distributed via DNSBL so mail systems can classify or reject messages containing those domains.

Even so, passive listing has structural constraints that you cannot “tune away”:

Listing is not removal

A domain can be listed and still resolve, still host a phishing kit, still collect credentials, and still reach victims through channels that do not enforce that list (or enforce it inconsistently). This is not hypothetical - economic measurement research has shown that blacklisted domains continue to monetise due to non-universal use of blacklists and deployment delays (i.e., not everyone blocks, not everyone updates, not everyone blocks in the same way).

In the UCSD-led study Empirically Characterizing Domain Abuse and the Revenue Impact of Blacklisting, the authors found that blacklisting can reduce sales per domain - but blacklisted domains still generated revenue, driven by the reality that blacklists are not universally used and are sometimes only advisory (e.g., “spam folder” classification rather than hard blocking).

Listing has unavoidable latency at multiple points

Even high-quality lists face time gaps:

- detection gap (first seen → confirmed)

- publishing gap (confirmed → added to list)

- propagation gap (list updated → downstream systems refreshed)

- enforcement gap (system has list → control blocks in that context)

Spamhaus itself notes that even when a DBL delisting is processed immediately, some users may lag up to 24 hours in removing domains from their local systems.

That is not a criticism; it is physics and operations. DNS caching, local sync schedules, and heterogeneous deployments create delay.

Listing typically lacks full context

A domain list often contains only domains/hostnames (not full paths), which is a practical design choice but can limit precision against rapidly changing URLs and disposable landing paths. Spamhaus explicitly notes DBL listings include hostnames, not full URL paths.

In short: passive listing is an essential defensive layer, but it is not a terminating action.

Disruption and enforcement: how you stop the threat at its source

Disruption and enforcement focus on terminating adversary capability, not just warning about it. In practice, which means using the governance and control points where domain-enabled abuse can be stopped:

- registrar/registry suspension, clientHold, serverHold or removal from the zone

- hosting provider takedown (content removed or account terminated)

- DNS changes (sinkholing, nameserver changes, record removal)

legal seizure orders and coordinated infrastructure dismantling

Two public-sector examples illustrate the difference - and the scale.

National-scale disruption: fast takedown works because it removes the infrastructure

UK National Cyber Security Centre describes Active Cyber Defence services as operating “behind the scenes” to block cyber-attacks before they reach targets, protecting organisations automatically after registration. In its Annual Review 2025, the NCSC reports its Takedown Service removed cyber-enabled commodity campaigns at scale and, critically, at high speed:

- 79% of confirmed phishing attacks targeting UK government departments were resolved within 24 hours of detection

- 50% were taken down in under 1 hour

Those numbers reflect something passive listing cannot do by itself: make the malicious site unreachable quickly enough to materially reduce victim volume in the “golden hours” of an attack.

Ecosystem enforcement: upstream contractual obligations can produce mass suspensions

ICANN’s 2024 DNS abuse contract amendments (for gTLD registries and registrars) formalised obligations requiring mitigation actions aimed at stopping or disrupting well-evidenced DNS abuse.

In the first six months of enforcement (5 April to 5 October 2024), ICANN Contractual Compliance reported:

- 192 DNS abuse mitigation investigations initiated

- 154 investigations resolved resulting in suspension of over 2,700 domain names

- disabling of over 350 phishing websites

This is enforcement at the control plane: not “flagging,” but compelling action that removes abusive domains from operation.

Law enforcement disruption: seizure and sinkholing deny attackers their infrastructure

Enforcement can also be judicial. For example, U.S. Department of Justice reported the unsealing of a warrant authorising the seizure of 41 internet domains used in a Russian intelligence spear‑phishing operation - explicitly “depriving them of the tools of their illicit trade.”

Similarly, a DOJ-led botnet operation described seizure warrants enabling the Federal Bureau of Investigation to take control of domains and redirect traffic to disrupt botnets - an action explicitly defined there as “sinkholing.”

This is the core superiority of disruption: it changes reality on the Internet. Listing changes metadata; disruption changes reachability.

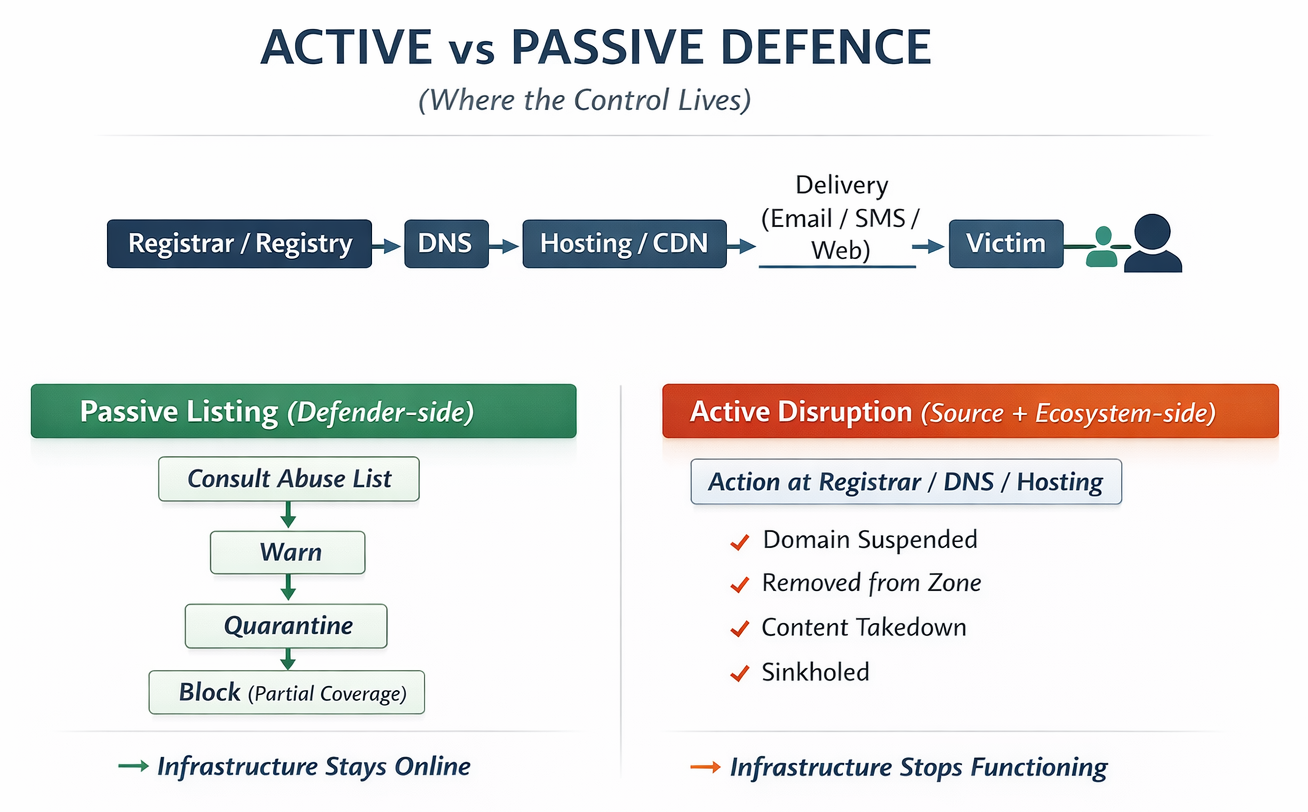

Active versus passive defence: two fundamentally different models

One way to clarify the difference is to frame it as where the control is applied.

- Passive defence primarily modifies the defender’s local decision-making (“block / warn / score”) based on threat intelligence.

- Active disruption modifies the attacker’s operating environment (“remove / disable / seize”) by acting on infrastructure and governance points.

NCSC’s description of Active Cyber Defence highlights exactly this idea: automated, behind‑the‑scenes services that block attacks before they reach targets and protect users automatically.

NCSC’s description of Active Cyber Defence highlights exactly this idea: automated, behind‑the‑scenes services that block attacks before they reach targets and protect users automatically.

Here is a simple diagram

The strategic implication is straightforward:

Passive defence reduces exposure probabilistically; active disruption reduces attacker capability deterministically (until reconstituted).

Lookalike domains: limiting the blast radius of typosquatting, combosquatting, and homographs

Lookalike domains are not an edge tactic. They are a durable operating model because they exploit two facts:

1. Users struggle to accurately parse URL identity.

2. Many lookalike domains remain online for a long time, often unremediated.

Users are measurably vulnerable to “look-alike” URL confusion

A CHI 2020 usable-security study found that participants correctly identified the real host identity 93% of the time for normal URLs - but only 40% for obfuscated “look‑alike” URLs.

That is a huge attack surface: even perfect awareness campaigns cannot rely on humans to consistently parse complex URLs correctly.

Combosquatting can be extremely long-lived

A longitudinal measurement study of combosquatting (domains combining a brand with extra tokens like “secure-,” “login-,” “support-”) found:

- almost 60% of abusive combosquatting domains live for more than 1,000 days

- public blacklist appearance can lag: 20% of abusive combosquatting domains appeared on a public blacklist almost 100 days after first observation (in their DNS data)

This directly supports the case for disruption: if a lookalike can stay active for years, relying on list-based deterrence alone is strategically insufficient.

Practical methods to reduce lookalike impact - and where disruption fits

There is no single control that “solves” lookalikes. The best results come from combining prevention, monitoring, and fast remediation.

Prevent and harden what you control (your own domains):

- For domains that do not send email, UK government guidance recommends explicit technical measures in DNS: SPF -all, DMARC reject policy, empty DKIM records, and null MX - explicitly to prevent spoofing and phishing abuse of unprotected domains.

- CERT-SE similarly recommends enabling SPF and deploying DMARC (starting in monitor mode, then considering blocking) and describes a real-world case where lack of SPF enabled spoofing - followed by contacting the hosting provider to take down the phishing site and preparing a police report.

These measures do not stop someone registering yourbrand-support.com, but they do shut down the quite common and damaging path of sending spoofed email directly from your legitimate domain space.

Reduce the opportunity space (defensive registration and policy):

- The Swedish Internet Foundation explicitly recommends reducing the risk of scam registrations by registering domains with incorrect spellings of your trademark.

- The same organisation has warned (in a Swedish case context) that criminals register misspelled .se domains to create email addresses like real companies’ addresses, used in CEO fraud scenarios. This is a pragmatic way to reduce attack surface - especially for high-volume brand abuse.

Enforce and recover when abuse occurs (legal + contractual levers):

- WIPO positions UDRP as an online enforcement tool to reclaim infringing domains used for consumer deception (“cybersquatting”), and notes WIPO’s large caseload and the ability for registrars to implement decisions without local court involvement.

UDRP is not “fast disruption” (often measured in weeks/months), but it is a critical enforcement tool when the domain is durable and economically valuable to the attacker.

Mitigate homograph risks (IDNs and confusables):

- The Unicode Consortium’s security guidance documents how confusable characters can create spoofing risks where a URL is one domain but belongs to another - a known risk class in IDN homograph attacks.

This is especially relevant for lookalikes that are not simple ASCII typos.

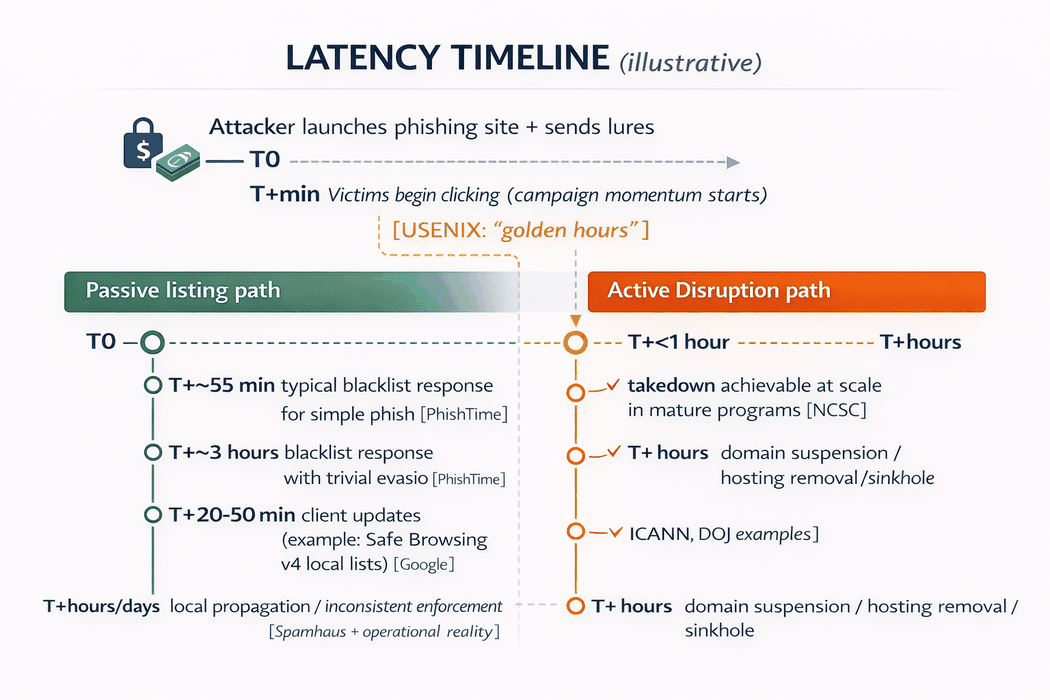

Beating latency: why disruption outperforms abuse-list updates in the “golden hours”

If you want one data-driven reason disruption outperforms listing, it is this:

Most malicious sites live on timelines that are shorter than list freshness guarantees - and attackers intentionally exploit that gap.

The attacker’s clock is fast

A large-scale phishing-site lifespan study (WWW 2025) analysed 286,237 phishing URLs and found:

- average lifespan: 54 hours

- median lifespan: 5.46 hours (many disappear quickly, while a minority persist much longer)

In parallel, Sunrise to Sunset (USENIX Security 2020) measured end-to-end phishing campaign lifecycles and found the average campaign from start to last victim takes 21 hours, with meaningful victim volume concentrated early.

The defender’s list update clock is slower (and sometimes structurally stale)

Google’s own Safe Browsing migration documentation explains that in v4, a “typical client takes 20 to 50 minutes” to obtain the most up-to-date threat lists, and that data staleness materially reduces protection; it also notes that 60% of sites that deliver attacks live less than 10 minutes, and estimates 25–30% of missing phishing protection is due to staleness.

Even if your organisation uses high-quality abuse data, list-based controls will always have a freshness problem somewhere in the pipeline.

Blacklisting delay is measurable - and evasion makes it worse

The USENIX Security 2020 PhishTime study measured blacklist response times and showed:

- average response ~55 minutes for unsophisticated phishing websites

- common evasion (e.g., URL shorteners) delayed blacklisting up to an average of 2 hours 58 minutes, and such sites were up to 19% less likely to be detected

This is exactly why “just list it” fails in practice: the economics of phishing reward the attacker for harvesting victims during the delay window.

Disruption closes the window by changing reachability

When a registrar, registry, or hosting provider disables the infrastructure, the attack collapses for all potential victims - not just those protected by a particular filter.

The NCSC describes takedown as removing malicious websites “at scale and in near real time,” explicitly to limit harm before it occurs, and reports sub-hour removal for half of confirmed phishing attacks in their target set.

ICANN’s enforcement data similarly shows that upstream compliance actions can result in domain suspensions and phishing site disablement at scale.

Here is a simplified timeline view of the latency issue:

Comparative analysis: disruption/enforcement vs passive listing

The table below contrasts the two approaches as security strategies. “Passive listing” is represented by blocklists/abuse datasets (e.g., Spamhaus DBL). “Disruption/enforcement” covers takedown, suspension, sinkholing, registry/registrar compliance, and legal seizure.

|

Attribute |

Disruption / enforcement (takedown, suspension, sinkhole, seizure) |

Passive listing (abuse lists / reputational datasets) |

| Primary objective | Terminate malicious infrastructure (reduce capability) | Flag known-bad infrastructure (reduce exposure) |

| Where it acts | Upstream control points: registry/registrar, DNS, hosting, legal orders | Downstream: mail filters, browsers, proxies, endpoint policies |

| Speed to reduce victimisation | Can be minutes-to-hours in mature programs (e.g., half <1h) | Often bounded by detection + publishing + propagation; can be hours or more, and evasion increases delays |

| Scope of impact | Internet-wide for that infrastructure: the site/domain stops functioning for everyone until reconstituted | Limited to the ecosystems that consume the list, update it, and block (non-universal) |

| Impact on threat actors | Direct cost imposition: forces rebuild, increases operational friction, enables attribution/investigation | Often absorbed via churn and substitution; blacklisted domains can continue monetising where lists are not enforced |

| Resistance to list-latency and "disposable" domains | Strong: disabling infrastructure ends the current attack instance even if it was “zero-day” | “Scale + coverage”: layered detection and filtering, plus retrospective intelligence Weak-to-moderate: works best against repeat infrastructure; struggles in the “golden hours” and with evasion |

| Lookalike domain problem | Can remove persistent lookalikes via registrar/registry action or disputes; complements defensive registration | Helps once discovered - but many lookalikes are long-lived and can appear on public blacklists late |

| Best use in a modern programme | “Terminate + prevent recurrence”: takedown + enforcement + hardening + monitoring | “Scale + coverage”: layered detection and filtering, plus retrospective intelligence |

The domain disruption lifecycle: a model that terminates threats, not just flags them

A mature disruption capability is not a single action; it is a repeatable lifecycle that outpaces attacker churn and abuse-list latency.

Here is a practical lifecycle view, aligned to how national and ecosystem actors describe their services:

DOMAIN DISRUPTION LIFECYCLE

1) Detect

- user reports, telemetry, threat intel feeds, brand monitoring (NCSC uses multiple feeds; CERT-SE describes incident discovery workflows)

2) Validate (fast triage)

- confirm abuse, capture evidence, classify as phishing/malware/etc.

- determine control points (domain vs hosting vs both)

3) Choose leverage

- registrar/registry: suspension / hold / remove from zone

- hosting: content/account takedown

- DNS change: sinkhole / redirect (law enforcement context)

- legal path: seizure warrant / coordinated operation

4) Execute disruption

- make the domain stop resolving or the site stop serving payloads

- verify from multiple vantage points

5) Measure impact and prevent recurrence

- monitor re-registration and lookalike drift

- harden brand domains (SPF/DMARC, defensive registrations)

- pursue enforcement for persistent actors / repeat infrastructure

Three public references reinforce why this lifecycle works:

- NCSC explicitly describes services that block attacks before they reach targets, and a takedown service that removes malicious sites at scale and speed.

- ICANN enforcement shows registrar/registry mitigation can produce thousands of suspensions and hundreds of phishing site disablements in months - evidence that upstream levers scale.

- The Swedish Internet Foundation describes domain deactivation mechanisms where a domain can be removed from the zone file (i.e., stops resolving) and later deregistered, illustrating how registry-level lifecycle control can terminate reachability.

This is why, in operational terms, disruption is closer to remediation than detection.

Closing thoughts: listing is a layer - disruption is the stopping function

Abuse lists such as those provided by Spamhaus contribute real value: they raise baseline safety, scale across organisations, and add immediate filtering capability in email and web stacks.

But the evidence is clear on three strategic realities:

- Attack lifetimes are short and front-loaded. Median phishing site lifespan can be hours, and campaign windows can be ~1 day, making delay extremely costly.

- List-based defences will always have freshness and adoption gaps, and attackers intentionally exploit those gaps through evasion and churn.

- When you remove or disable the domain/infrastructure, you stop the threat at its source - which is why takedown programmes (NCSC), contractual enforcement (ICANN), and judicial actions (DOJ/FBI sinkholing and seizures) are demonstrably impactful.

For organisations serious about reducing victimisation - not just reporting it - disruption and enforcement are the capabilities that change outcomes. Passive listing remains valuable, but it performs best as supporting intelligence in a broader strategy that terminates malicious infrastructure upstream - the kind of strategy Excedo Networks designs for real-world, domain-enabled threats.